Andrei Şerban: Când am început să lucrez la acest proiect, mi-era teamă că nu voi rezona cu anumite aspecte ale piesei. Personal, nu sunt un activist politic, nici măcar un liberal, şi nu cred că teatrul trebuie să facă vreun fel de declaraţie. Propaganda produce artă mediocră deseori. Dar Kushner este un scriitor foarte important, implicat în activism politic şi în apărarea cauzei tuturor grupurilor care resimt nedreptatea celor de la putere.

Însă ceea ce m-a atras la Îngeri nu a fost aspectul social, sexual sau politic, ci cel uman. Într-o lume în criză, lupta oamenilor cu ei înşişi pentru a-şi găsi identitatea, lupta contra izolării şi a exilării din viaţă, sunt teme ce mă interesează direct. Şi dacă mie piesa îmi spune ceva, ea ar putea interesa pe fiecare; căci împărtăşim dorinţa de unitate, sănătate şi armonie. Punând întrebări, de la cele obişnuite şi banale, la cele spirituale, Kushner merge periculos de departe, punând chiar la îndoială Biblia.

Şi chiar dacă unele personaje ale piesei sunt homosexuali afectaţi de virusul HIV, eu sunt convins că această piesă vorbeşte despre suferinţă şi empatie la un nivel mult mai profund şi metafizic. Eu nu sunt homosexual şi nu susţin activ această cauză, dar totuşi problema eticii despre cum ne comportăm cu bolnavii şi invalizii mă priveşte şi pe mine. Ajutorul, compasiunea şi rugăciunea sunt esenţiale.

R.S.: Cum ar putea piesa Îngeri în America să atragă publicul în Ungaria?

A.Ş.: Putem vedea astăzi cum se anulează o democraţie; noua putere din România şi cea din Ungaria au preluat exact partea negativă a epocii Reagan. Cum să ţii timpul în loc, cum să te întorci înapoi - este exact ceea ce politicienii încearcă să facă în acele ţări. În România de curând a avut loc o lovitură de stat, o încercare de a aduce trecutul înapoi. Ceea ce nu realizează aceşti politicieni idioţi este că nu poţi întoarce timpul, este o lege cosmică. Conflictul din Îngeri este între cei care vor să progreseze şi cei care vor să se întoarcă în timp, o oglindă a ceea ce se întâmplă astăzi, cel puţin în Europa de Est.

R.S.: Sunt două piese de teatru diferite. Cum se poate rezolva problema comprimării textului dramatic?

A.Ş.: Este pentru prima dată când aceste piese lungi sunt făcute împreună într-o singură seară. În New York se joacă în seri diferite. Am fost conştient că unele aspecte ale labirintului complex creat de Kushner s-ar putea pierde prin traducere. De aceea am făcut o selecţie cu ceea ce s-ar preta mai mult pentru publicul maghiar, teme ce ar avea o reacţie imediată aici, atfel încât nimeni nu va pleca de la teatru gândindu-se că piesa este doar despre America.

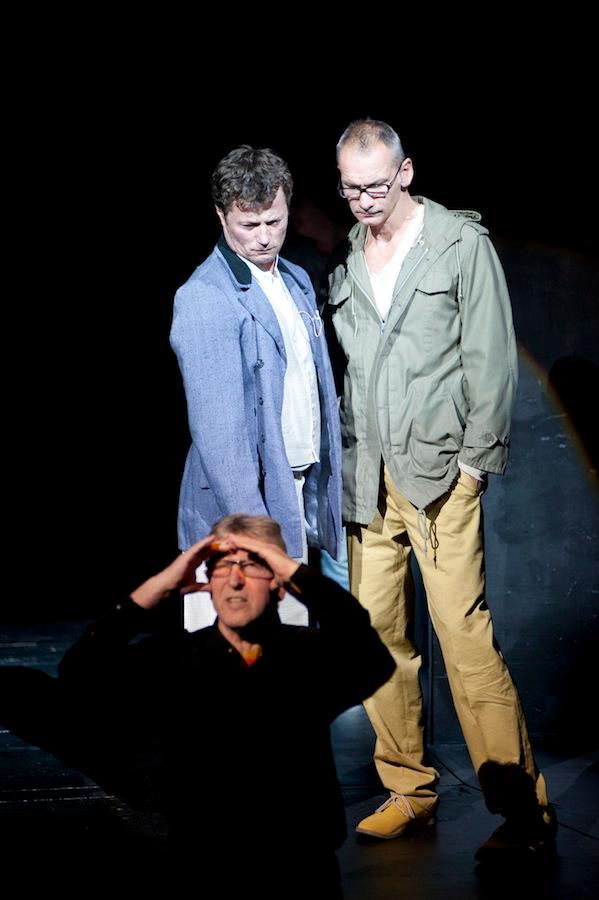

R.S.: La conferinţa de presă de la Teatrul Naţional din Budapesta aţi spus "Este timpul să ne punem imaginaţia la contribuţie, pentru că avem prea puţini bani pentru a face teatru." Cum a fost să lucraţi cu actorii maghiari în aceste condiţii financiare?

A.Ş.: Am lucrat în tot felul de situaţii de la avangardistul La Mama unde nu aveam nici un buget alocat, la Broadway şi Metropolitan pentru un buget colosal! Omul trebuie să înveţe să fie flexibil, să se adapteze, rămânând creativ. Desigur că am fost şocat când am ajuns la Budapesta şi am aflat că Teatrul Naţional a trecut printr-o mare reducere de buget. A fost supărător. Dar am colaborat minunat cu actorii şi am încercat să ne concentrăm mai mult pe ceea ce se întâmplă între noi, iar acest lucru s-a dovedit a fi o experienţă foarte plăcută. Sper ca în seara premierei să avem ceva de arătat, măcar nişte costume!

R.S.: Spectacolul dumneavoastră precedent Trei surori a vorbit despre iluzii şi minciuni care predomină viaţa cotidiană în Ungaria. Consideraţi că teatrul este un mod de a înţelege mai bine lumea?

A.Ş.: Răspunsul este un da hotărât. De ce? Întrucât ceea ce încercăm noi pe scenă ar putea fi util pentru cei ce ne văd. Tocmai fiindcă trăim într-o lume fragmentată şi din această cauză teatrul contemporan este divizat şi confuz; el nu se adresează necesităţii şi dorinţei majorităţii oamenilor pentru o altă posibilitate, alt dialog; teatrul e un loc de a găsi o calitate mai bună a impresiilor, dorinţa de a aduce împreună altceva decât deziluzia şi disperarea... Lucrez în teatru cu acest ţel în minte că ar putea face bine cuiva. De aceea îmi asum riscul de a folosi cuvinte precum credinţă şi speranţă (cuvinte care nu mai sunt la modă în vocabularul de azi) din dorinţa de a împărtăşi totul cu actorii şi publicul care sunt avizi de ceva mai mult, avizi de o emoţie diferită faţă de ce e sumbru, cinic şi pesimist. Într-adevăr, Cehov ne arată cât de absurdă şi tragi-comică este condiţia noastră, el a fost un chirurg care a operat pe psihicul nostru bolnav, dar a fost un doctor milos. Îndurarea şi compasiunea sunt la fel de autentice ca şi cruzimea, iar întunericul există doar pentru că există şi lumina. Chiar şi la final, singure şi disperate, cele Trei surori nu abandonează speranţa pentru o viaţă mai bună şi mai profundă. "Numai dacă am şti cum să trăim..." aceasta este o întrebare deschisă adresată tuturor.

R.S.: Sunteţi cunoscut pentru vizualitatea provocatoare şi felul în care reinterpretaţi pe scenă opere clasice cum ar fi tragedia greacă sau Cehov, Shakespeare. Care este dramaturgul dumneavoastră preferat, clasic şi contemporan?

A.Ş.: Dramaturgul meu preferat este, mereu, cel cu a cărui text lucrez în clipa respectivă, cel a cărui creaţie o pun în scenă. Trebuie să credem că prezentul este cel mai important şi că întreaga lume depinde de piesa noastră. Deşi este adevărat că teatrul este la marginea societăţii astăzi, trebuie să credem că mirarea, surpriza, şocul încă sunt posibile, şi că după ce pleci de la teatru, te vei simţii mai viu.

R.S.: Reîntorcându-ne în timp, prima transpunere pe scenă a lui Iulius Cezar în maniera tradiţională kabuki a provocat un imens scandal. Aţi putea să-mi spuneţi mai multe despre acea experienţă?

A.Ş.: Era vorba despre atitudinea tinereţii, de a fi înaintea timpului său, de a fi împotriva tradiţiei. Totul se schimbă atât de repede, iar azi este un déjà vu, un mod învechit de a-l aborda pe Shakespeare. Dar atunci a iscat un scandal în România. Cum să menţii floarea tinereţii vie şi proaspătă mai târziu în viaţă, aceasta este pentru mine ACUM adevărata întrebare, mai mult decât "a fi sau a nu fi"!

R.S.: În anii '70 aţi devenit unul dintre cei mai remarcabili directori de teatru din Statele Unite. Ce a însemnat pentru dumneavoastră compania de teatru "La MaMa"?

A.Ş.: La MaMa a fost şansa izbăvitoare pentru mine. Dacă aş fi rămas în România, nu aş fi văzut în veci orizonturi atât de largi, nu aş fi avut şansa să experimentez liber şi să-mi învăţ meseria, nu i-aş fi întâlnit niciodată pe Brook şi Grotovski, iar fără aceşti extraordinari profesori, viaţa mea ar fi luat o direcţie diferită. Fiecare din noi avem nevoie de un model în viaţă, toţi avem nevoie de o figură paternă, trebuie să ne găsim un exemplu care să ne inspire.

Cât de trist este faptul că în ziua de azi tinerii sunt atât de autosuficienţi, cred că lumea s-a născut o dată cu ei.

R.S.: Aţi locuit şi lucrat la Paris timp de câţiva ani. În care măsură vă consideraţi un discipol al lui Peter Brook?

A.Ş.: Poate părea ciudat în lumea noastră fără credinţă să afirm că Brook a fost un fel de Dumnezeu pentru mine. Dar a fost, în sensul în care orice geniu este dumnezeiesc! Majoritatea dintre noi, cei care am lucrat cu Brook, sunt de părere că am fost în prezenţa unui profesor nemaipomenit, chiar dacă el nu se considera astfel. Am învăţat mai mult de la el într-un an decât în toţi anii petrecuţi în şcoală! Când a fost întrebat de cheia secretă a abilităţilor sale, Brook a răspuns - "Eu nu vă pot dezvolta, pot doar crea condiţii în care să vă dezvoltaţi voi singuri". A avea nevoie, a-ţi dori, a face eforturi, acestea sunt cele trei verbe pe care le-am învăţat de la el. Ca un fermier înţelept, el ne-a ajutat să smulgem toate buruienile din domeniul personal, să ne purificăm corpurile din nou, să scăpăm de iluzii şi minciuni care sunt atât de prezente în meseria noastră, să ne conştientizăm manierismele, şi să începem cu forţe proaspete de fiecare dată, de la zero, cultivând pământul cu seminţe noi. "Câmpul nostru artistic ar trebui arat periodic, împreună, aşa cum pământul este arat."

Singuri nu putem face nimic. Avem nevoie unii de alţii ca să arăm acest pământ întins care aparţine tuturora - teatrul! Atingerea divinităţii nu vine ca un cadou ieftin, când o chemăm noi! Trebuie să plătim pentru ea. CUM? Plata este efortul de a înţelege umanitatea, să te pui în locul altcuiva. Pentru a juca roluri, în viaţă sau pe scenă, trebuie să-i cunoşti pe aceşti "străini" de dinafară şi de dinăuntru. Trebuie să lucrăm, să facem greşeli, să o luăm de la capăt, să căutăm. Misiunea noastră este comparabilă unei lungi călătorii cu vaporul pe mare, în care nu suntem pasageri pasivi, ci membrii ai echipajului, activi. În special în teatru trebuie să învăţăm să slujim şi altcuiva în afara propriului nostru orgoliu, în afara micului nostru interes egoist. Dorinţa de a atinge altceva, mai înalt. Acesta este esenţa a ce a însemnat Brook pentru mine.

R.S.: După mulţi ani de emigraţie ce v-a făcut să vă întoarceţi în România ca director artistic la Teatrul Naţional (din 1990 până în 1993=?

A.Ş.: M-am întors din naivitate fiindcă speram să schimb ceva, să-l trezesc pe bătrânul elefant instituţional numit Naţional şi să-i dau oxigen nou, dar la puţin timp după ce românii m-au primit cu aplauze şi trandafiri, am putut mirosi bălegarul, gunoiul ce stătea la rădăcina florilor. Pentru ei eram un american naiv, pe care ei îl puteau manipula în scopul lor egoist. Actorii nu-şi doreau să se reinventeze, nu le păsa de dezvoltare sau progres, vroiau doar să călătorească în străinătate la festivaluri, în locuri foarte frumoase unde erau invitate spectacolele mele. Devenisem un fel de ghid turistic pentru ei, iar asta nu era nici o plăcere pentru mine. Iar când Ministrul Culturii a început să impună o subtilă cenzură asupra alegerilor mele artistice, iar vechile şi stupidele jocuri politice au devenit evidente, a fost semnul că trebuia să plec şi să încep al doilea exil. Dar m-am întors mai târziu, fiindcă simţeam că am o responsabilitate asupra tinerei generaţii, în vreme ce situaţia din şcolile de teatru s-a înrăutăţit, am organizat ateliere speciale, intensive, de vară pentru a experimenta cu tinerii actori metode noi, la ţară, în natură, departe de civilizaţie. Aceste ateliere sunt cele mai importante pentru mine, deoarece îi transformă activ pe oamenii care participă la ele, mult mai mult decât repetiţiile la un spectacol de teatru.

R.S.: Ce părere aveţi despre teatrul românesc contemporan? Colaboraţi deseori cu el?

A.Ş.: Încerc să menţin legătura şi să mă întorc o dată pe an (când îmi permite orarul de la Columbia University din New York, unde predau actorie - o mare responsabilitate) şi ţin conferinţe sau fac un spectacol. Există o nevoie de educaţie, din cauza unui nivel alarmant de sărăcie şi pasivitate. Teatrul românesc trebuie să-şi găsească propriul stil din nou. Acum nu are nici o direcţie, nici un impuls, nici o dorinţă de a spune ceea ce contează. În timpul comunismului, prin împotrivire şi încercarea de a scăpa de cenzură, teatrul a căpătat energie şi vitalitate. În prezent acestea s-au pierdut şi deocamdată există multă confuzie şi doar din când în când câteva spectacole bune, dar sporadice.

R.S.: Ce impresie v-a făcut teatrul maghiar Kulturkamf, mai ales din prisma reacţiilor isterice ale extremei dreapta împotriva lui Alföldi Róbert?

A.Ş.: Alföldi este unic, iar din moment ce stă aici în mod sigur are nişte aşi în mânecă. Pentru mine este un paradox cum poate el să fie încă la Naţional după toate atacurile umilitoare de care a avut parte, iar ultimul fiind tăierea de buget! Exemplul pe care ni-l dă este în determinarea sa de a persevera şi a continua să lucreze în condiţii de stres şi în acest mediu ostil. Pasiunea lui pentru teatru este atât de mare, că poate depăşi obstacole imposibile. Se aseamănă cu Prior, rolul pe care îl joacă în Îngeri, care supravieţuieşte şi continuă să lupte în pofida tuturor îngerilor... Deviza lui pare să fie "noi continuăm să lucrăm, atâta timp cât nu închideţi teatrul nimic nu este irosit, fiecare experienţă poate fi de folos"! Arta triumfă, cel puţin până acum.

Andrei Şerban: When I started to work on this project, I was afraid that it could be hard for me to relate to certain aspects of the play. Personally I am not a political militant, not even a liberal; and I don't believe that theatre should make statements of any sort.

Propaganda often produces mediocre art. On the other side Kushner is a very important writer, and he is engaged in political activism and in defending the cause of all groups who feel the injustice of those in power. But what attracted me to Angels was not the social, sexual or political, but the human aspect. In a world in crisis, people struggling with themselves to find their identity, the struggle to fight isolation and exiled from life, this speaks to me directly... And if it speaks to me it could become everyone's concern; the longing for unity, health and harmony is to be shared by us. Asking questions, from the common and ordinary to the spiritual, Kushner goes quite dangerously far, to even challenge the Bible.

Also, even though some of the characters of Angels are gay, afflicted by AIDS, I am convinced that this play speaks about suffering and empathy on a deeper and more methaphisical level. I personally am not gay, and I am not actively committed to that cause; however, the ethical question of how we all treat those who are ill and disabled, concerns me as well. Help, compassion and prayer are most needed.

R.S.: How can Angels be of interest in Hungary?

A.Ş.: Look how a democracy is canceled, this is what this new power in Hungary and Romania learned in a bad way from the Reagan era.

How to keep time to a halt, how to go back-- is exactly what the politicians try to do here. In Romania there was recently a coup d'etat, trying to bring back the past. What these idiotic politicians don't know is that time can not return, it is a cosmic law.

The conflict in Angels is between those who want to progress and the ones who want to go back in time, a mirror of what happens today, at least in Eastern Europe.

R.S.: There are two different plays. How to solve the problem of dramatic text's reduction?

A.Ş.: It's for the first time that these long plays are done together in a single evening. In New York they are each performed in separate nights. Some aspects of the complex labyrinth that Kushner created could be lost in translation. This is why we made some cuts selecting what is the most appealing for a Hungarian audience, the themes which can have an immediate echo here, so nobody shall leave the theatre thinking the play is about America only.

R.S.: At the press conference of the National Theatre you said: It' s time to train our imagination because of having too little money for the spectacle. How challenging is it for you to work with Hungarian actors in these financial conditions?

A.Ş.: I worked in every kind of situation: from the avanguard La MaMa where we had zero money to Broadway and Metropolitan, for a budget made in gold! One has to learn to be flexible, to adapt and still be creative. Of course I was shocked when I arrived in Budapest to find out that the National really has suffered a big money cut. It was upsetting. But the actors were wonderful to work with and we tried to concentrate more on what happens among us and it became a very enjoyable experience.

I hope by the opening night we will have something to show, some costumes at least!

R.S.: Your previous interpretation of Three Sisters spoke about illusions and lies that determine life in Hungary today. Do you consider theater as a way for a better understanding of the world?

A.Ş.: The answer is a big yes. Why? Because what we attempt might do some good. Exactly because we live in this fragmented world, and because of that the contemporary theatre is divided and confused, it does not address the need and the longing of so many people for another possibility, another dialogue; theatre as a place to find a better quality of impressions, the wish to bring us together for something else than disillusion and despair... I work in theatre with this aim in mind: "that it might do some good". That is why I take the risk to use words like faith and hope, (words not in fashion in today's vocabulary) in the wish to share with actors and audience who are hungry for something more, hungry for a different emotion than the bleak, the cynical and the pessimistic. Yes, Chekhov does show how absurd and tragic-comic our situation is, he was a doctor who did make surgery on our sick psyche, but he was a compassionate doctor. The mercy and the compassion are just as true as the cruelty, and the darkness is there only because there is light. Even at the end, alone and desperate, the Three Sisters never abandon the hope in a better, more intelligent life. "If we only knew" how to live... this is an open question for all of us.

R.S.: You are known for your provocative visuality and the way you reinterpret classical works such as Greek tragedy or Chekhov, Shakespeare. Who is your favorite / classic and contemporary / playwright and why?

A.Ş.: My favorite playwright is the one that I am staging and working with at this moment. One has to believe that the present moment is the most important and that the entire world depends on our play. Even if it is true that theatre is at the margin of society today, we must believe that wonder, surprise, shock are still possible, that after leaving the theatre, you can feel more alive.

R.S.: Going back in the time your first Julius Caesar direction in the traditional kabouki manner caused a true scandal made you over. Could you talk about that experience?

A.Ş.: It was the attitude of youth, to be ahead of its time, to go against tradition. Everything changes so fast, and today it is déjà vu, old hat to approach Shakespeare this way. But back then it created a scandal in Romania. How to keep that flower of youth alive and fresh later in life, this is for me NOW the real question, more than "to be or not to be"!

R.S.: In the 70's you became one of the most prominent theatrical director in the U.S. How do you remember La MaMa Theater Company?

A.Ş.: La MaMa was for me the saving grace. If I would have remained in Romania, I would have never seen the big wide horizons, never given the chance to experiment freely and learn my craft, never met Brook and Grotovski, and without these great teachers, my life would have taken a different direction.

We all need to look UP at someone in the chain, we all have a father, have to find before us an example to inspire us.

How sad today that the young ones are so self sufficient, they believe the world was born with them.

R.S.: For some years you lived and worked in Paris. In which way do you consider a disciple of Peter Brook?

A.Ş.: It may appear strange in our faithless world to imply that Brook was a sort of God in my eyes. But he was, in a sense that any genius is god-like! Most of us who worked with Brook, believed that we were in the presence of a great teacher, even if he never considered himself being one. I leaned more from him in one year than during all my time in school! Brook said, when asked to give the secret key of his knowledge: "I can not develop you, I can only create conditions in which you can develop yourself". To need, to wish, and to make efforts, these were the three verbs I leaned from him. Like a wise farmer, he did help us to pool all the weeds in our personal field, to irrigate our body anew, to get rid of the illusions and lies which are so much part of our trade, to see our old habits, and start each time fresh, cultivating the ground with new seeds. "Our artistic individual field should be ploughed together as the earth is ploughed".

Alone we could do nothing. We needed each other to plow this vast ground that belongs to all of us--the theatre! To be "touched by grace" does not come as a cheap gift, simply when we call it! We need to pay for it. HOW? Payment is in the effort to understand humanity, to put oneself in the place of another. Playing roles, in life or on stage, one should know these "strangers" around us and also inside us. We need to work, to make mistakes, to start again, to search. Our mission is comparable to the long journey on a boat at sea, where we are not passive passengers, but active crew members. Especially in theatre we must learn to serve something else than our own vanity, our own small egotistic interest. The longing to reach for something else, for the higher. This is the essential Brook for me.

R.S.: After many years of emigration what did you make return to Romania as artistic director of the National Theatre from 1990 to 1993?

A.Ş.: I went back naively because I was hoping to do some good, to wake up the old sleepy institutional elephant called the National and to give it new oxygen, but soon after the Romanians received me with applause and roses, I could smell bad the manure, the shit that was at the flower's root. I was for them a naïve American they could manipulate for their little selfish scope. The actors did not want to re-invent themselves new, they didn't care to develop and progress, they only wanted to travel abroad to festivals, in very nice places where my productions were invited. I became a tourist guide for them, and that was no fun for me. And when the Ministry of Culture started to impose a subtle censorship on my artistic choices, and the old stupid political games became obvious, it was the sign to leave and start a second exile. But I returned later, since I felt a responsibility towards the young generation, since the theatre schools got worse and worse, I organized special summer intensive workshops to experiment with them in new ways, outside in the country side, in the nature away from the establishment. These workshops are the most important for me, since they actively transform the people that participate, much more than a show in the theatre does.

R.S.: What do you think about the Romanian theater nowadays? Do you work often there?

A.Ş.: I try to keep in touch and go back once every year (when my schedule allows from Columbia University in New York, where I am teaching students in acting --a heavy load) and do either a production or give lectures and conferences. There is a need for education, because of an alarming level of spiritual poverty and passivity. The Romanian theatre has to find its own voice again. It has no direction now, no urge, no need to say anything that matters. During communism, resisting and trying to escape censorship, theatre found energy and vitality. Today that is lost and for the moment there is a lot of confusion and only from time to time some sporadic good productions.

R.S.: What are your thoughts on the Hungarian Kulturkampf, especially on the hysterical reflections of the extrem-right against Alföldi Róbert

A.Ş.: Well, Alföldi is unique, he must have some secrets in his sleeve that keep him where he is. For me it's a paradox how he could still be at the National after all the humiliating attacks he received, the last being the budget cut! The example he gives us is in his determination to persevere and continue to work under extreme pressure and this hostile environment. His passion for the theatre is so strong that he can overcome impossible obstacles. He is like Prior, the role he plays in Angels, who survives and keeps fighting in spite of all angels... His message seems to be "we keep working, as long as they don't close the theatre nothing is ever wasted, every experience can be of use!" Art is winning, at least so far.