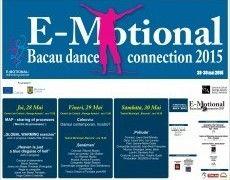

In May 2015, she was invited as an artist in residence at E-Motional Bacău Dance Connection, an E-Motional: rethinking dance project, where she was hosted by the "George Apostu" Cultural Centre through the ArtistNe(s)t residency programme launched in 2004 by the Gabriela Tudor Foundation.

The European project E-Motional: rethinking dance was developed with financial support from the Culture programme of the European Union and the Ministry of Culture from Romania.

Beatrice Lăpădat: First of all, please tell us about the creative process behind Global War(ming), the performance you presented at E-Motional Bacău Dance Connection, 2015. What was the trail you followed beginning with the moment you came to Bacău as an artist in residence?

Natalia Wilk: I could say this process debuted approximately 20 years ago, when I started my professional swimming training. Since then, I have been practicing this sport on a regular basis and my interest in water has grown further, including aquatic techniques such as watsu, water dance, liquid body. I also worked as a lifeguard at some point.

As I am educated in political science as well, it's no wonder that my interest in water soon became a social concern. That's how it started. Then I met Isabelle Schad and discovered that water issue was very close to her approach to embryology. This fascination thus turned into a language that I knew I would pay more attention to in my own work.

Therefore, Global War(ming), the short piece I presented at Bacău, at the "George Apostu" Cultural Centre, was the result of my intense focus on two aspects. First, it had to do with the relation between body and physical water. Secondly, there was a kind of "humoresque" approach, if I may call it so, to my own interrogations about how to live inside the Global Warming ocean.

B.L.: To what extent has the atmosphere in Bacău influenced the construction of your performance?

N.W.: I was surprised when I arrived in Bacău and discovered that my artistic proposal - which was a very "watery" one - met the conditions of an almost dry river. I was also told that the closest healing springs were out of town. I found that irony quite meaningful and played with it in my solo. I wanted to transmit something about the wish to return to waters, the wish to understand the streams so that human activity won't make water disappear in the end.

After all, everything is just one great pretense - we are not actually underwater during the Global War(ming) exercise. The image of a dry landscape, which I found materialized in Bacău, helped me clarify my final concept.

Natalia Wilk: I could say this process debuted approximately 20 years ago, when I started my professional swimming training. Since then, I have been practicing this sport on a regular basis and my interest in water has grown further, including aquatic techniques such as watsu, water dance, liquid body. I also worked as a lifeguard at some point.

As I am educated in political science as well, it's no wonder that my interest in water soon became a social concern. That's how it started. Then I met Isabelle Schad and discovered that water issue was very close to her approach to embryology. This fascination thus turned into a language that I knew I would pay more attention to in my own work.

Therefore, Global War(ming), the short piece I presented at Bacău, at the "George Apostu" Cultural Centre, was the result of my intense focus on two aspects. First, it had to do with the relation between body and physical water. Secondly, there was a kind of "humoresque" approach, if I may call it so, to my own interrogations about how to live inside the Global Warming ocean.

B.L.: To what extent has the atmosphere in Bacău influenced the construction of your performance?

N.W.: I was surprised when I arrived in Bacău and discovered that my artistic proposal - which was a very "watery" one - met the conditions of an almost dry river. I was also told that the closest healing springs were out of town. I found that irony quite meaningful and played with it in my solo. I wanted to transmit something about the wish to return to waters, the wish to understand the streams so that human activity won't make water disappear in the end.

After all, everything is just one great pretense - we are not actually underwater during the Global War(ming) exercise. The image of a dry landscape, which I found materialized in Bacău, helped me clarify my final concept.

B.L.: Has the contact with this specific environment provided you with completely unexpected ideas?

N.W.: On the one hand, I knew from the very beginning what were the instruments and concepts I wanted to work with, but in site I was confronted with the reality of a dry river, therefore I acted according to that. It was very important, because it helped me to understand why I was not placing my performance in real water. Thus, I had a revelation about the reason why my own body became the imaginary ocean I would love to swim in.

B.L.: Global War(ming) transmits a very strong female empowerment message. Is your project purposely attached to a feminist statement?

N.W.: I do not define myself as a feminist - neither privately, nor artistically. My statement, then, is far from any feminist message. My message is rather connected to one's power and status of their own and for their own. I'm happy, though, to hear this kind of interpretation, as one of the characters I dealt with in preparation for my solo was Little Mermaid from Disney. So, if someone sees my performance as a manifesto of "female" or "matriarchal" attitude, that's fine, especially since I too have a close relation to nature in this project, which is a feminine approach rather than a masculine one.

B.L.: Do you think that themes such as environment or feminism are in danger of becoming redundant or overexposed?

N.W.: I guess feminism and queer movement are quite popular now. But since I am not working with these themes, I cannot truly make a statement in relation to them.

In what concerns the environment, I think this issue could never be overdone. Actually, I think that whatever you create as an artist - whether it is through a BMC (Body-Mind Centering), embryological or economical perspective (talking about the policy of food, planting etc.) - it will always be about the environment. And I would say it will never be too much until we reach the moment people understand the problems and facts involved in the narration written by strong companies and capitalistic rules. It is not very easy to keep your mind open and sharp in the confrontation with the current methods by which people are ruled and deceived. I'm not saying that I am super aware of that myself. The thing is to try to stay alert and make your own choices.

N.W.: On the one hand, I knew from the very beginning what were the instruments and concepts I wanted to work with, but in site I was confronted with the reality of a dry river, therefore I acted according to that. It was very important, because it helped me to understand why I was not placing my performance in real water. Thus, I had a revelation about the reason why my own body became the imaginary ocean I would love to swim in.

B.L.: Global War(ming) transmits a very strong female empowerment message. Is your project purposely attached to a feminist statement?

N.W.: I do not define myself as a feminist - neither privately, nor artistically. My statement, then, is far from any feminist message. My message is rather connected to one's power and status of their own and for their own. I'm happy, though, to hear this kind of interpretation, as one of the characters I dealt with in preparation for my solo was Little Mermaid from Disney. So, if someone sees my performance as a manifesto of "female" or "matriarchal" attitude, that's fine, especially since I too have a close relation to nature in this project, which is a feminine approach rather than a masculine one.

B.L.: Do you think that themes such as environment or feminism are in danger of becoming redundant or overexposed?

N.W.: I guess feminism and queer movement are quite popular now. But since I am not working with these themes, I cannot truly make a statement in relation to them.

In what concerns the environment, I think this issue could never be overdone. Actually, I think that whatever you create as an artist - whether it is through a BMC (Body-Mind Centering), embryological or economical perspective (talking about the policy of food, planting etc.) - it will always be about the environment. And I would say it will never be too much until we reach the moment people understand the problems and facts involved in the narration written by strong companies and capitalistic rules. It is not very easy to keep your mind open and sharp in the confrontation with the current methods by which people are ruled and deceived. I'm not saying that I am super aware of that myself. The thing is to try to stay alert and make your own choices.

B.L.: What was the impact you aimed at by performing Global Warm(ing) at E-Motional Bacău Dance Connection?

N.W.: I simply wished people understood it as an invitation to swim in their own ocean, by which I mean an imaginary liquid environment, not far from the image of a return to the maternal womb. Basically, my message was about waiting for the great cleansing wave of disaster. If we head towards destruction, maybe it could help us to go back to point zero, to the core. Water-zen.

B.L.: Please tell us what your interference with E-Motional Bacău Dance Connection and ArtistNe(s)t has meant for your artistic evolution.

N.W.: This event was very important for me, as it was the first residency I accomplished on my own, working independently on the material. In addition to the discoveries related to the piece itself, I found out a lot about my own manner of working, about the importance of daily practice and concentration. In a way, that was the first time I had the opportunity to define some specific aspects in the sphere of my artistic practice.

B.L: In your opinion, what is the main point that establishes a connection between dance and performance in Poland and Romania today?

N.W.: On the one hand, I feel there are many points in common but, on the other hand, I am also aware of the fact that there are several differences. One can see that there are some similar stages of evolution in the history of these two countries, among the most recent being the accession to the European Union and the USA military bases.

I can see that Romania is very active in producing new networks and artistic connections, whereas the Polish model is a little different in this sense. I also perceive a strong influence that theatre exerts upon performative arts in both countries. In my opinion, both Polish and Romanian artists have a lot to say in this area, without necessarily following trends from abroad. Romania and Poland are both important emerging countries in the dance field and they constantly propose fresh formulas and new approaches. I also think Romania is connected to French art on a deeper level, while Poland is rather marked by the Anglophone area of influence.

I trust a lot in the power of the countries belonging to Central Europe or the Balkans. I would rather explore these places than follow the same already strongly "established" countries in the dance world.

B.L.: What are you expecting to find in Romania the moment you return here?

N.W.: If I could come back, I would love to see more places where dance can be created. I would also love to meet other participants in the same residency programme in Bacău from the previous years and take part in a festival that facilitates artistic practice exchange. I also hope Romania opens new places to support small, private initiatives instead of closing them down. Basically, I'm looking forward to witnessing the development and support of those good ideas already present in the dance field. It would be a pleasure to come to your country again even if these concepts were still under construction. I'd like to return with more knowledge than I possess at the present moment, so that I could explore something really connected with the country and its people.

N.W.: On the one hand, I feel there are many points in common but, on the other hand, I am also aware of the fact that there are several differences. One can see that there are some similar stages of evolution in the history of these two countries, among the most recent being the accession to the European Union and the USA military bases.

I can see that Romania is very active in producing new networks and artistic connections, whereas the Polish model is a little different in this sense. I also perceive a strong influence that theatre exerts upon performative arts in both countries. In my opinion, both Polish and Romanian artists have a lot to say in this area, without necessarily following trends from abroad. Romania and Poland are both important emerging countries in the dance field and they constantly propose fresh formulas and new approaches. I also think Romania is connected to French art on a deeper level, while Poland is rather marked by the Anglophone area of influence.

I trust a lot in the power of the countries belonging to Central Europe or the Balkans. I would rather explore these places than follow the same already strongly "established" countries in the dance world.

B.L.: What are you expecting to find in Romania the moment you return here?

N.W.: If I could come back, I would love to see more places where dance can be created. I would also love to meet other participants in the same residency programme in Bacău from the previous years and take part in a festival that facilitates artistic practice exchange. I also hope Romania opens new places to support small, private initiatives instead of closing them down. Basically, I'm looking forward to witnessing the development and support of those good ideas already present in the dance field. It would be a pleasure to come to your country again even if these concepts were still under construction. I'd like to return with more knowledge than I possess at the present moment, so that I could explore something really connected with the country and its people.

Photo credits: Anca Mihăilă, Mari Bucur