The Act of Killing is one of those good movies you wished you hadn't seen. Not because of the obvious horrors they unravel but because of the special way they make you connect with the people involved and the reality of what happened to them. The way in which they magnify your perspective (directorial vision is crucial for this part) and show you that what you perceived to be black and white is actually a suffocating murky gray. I remember only one other movie that managed to stir inside me the same kind of uneasy feeling, the feeling that, while the movie was no doubt a masterpiece, I would have been better off not seeing it, that in the end, as tribal people used to fear, the camera (by what it showed me) had managed to steal away some piece of my soul. That other movie was called Grizzly Man and, while researching for this review, I wasn't too surprised to find out that Werner Herzog, the director of Grizzly Man, was one of the producers of The Act of Killing.

In both movies, the reason for this uneasiness is the special nature of the rapport between documentary and reality, and the powerful way in which cinema, as these two examples prove, can transform fiction into something very real. In the case of The Act of Killing, this kind of disturbing transformation is best understood by drawing a parallel to method acting. A method actor aims at creating in himself (the actor not the character) the feelings and inner life of the character he is about to play. Imagine now, that an executioner is asked to play the part of an executioner, and not just any executioner, but of himself! Let your imagination go even further, as director Joshua Oppenheimer has, and set-up this acting exercise in a twisted moral universe, in which the executioner has not been punished but declared a national hero and thus, has no reason (neither guilt nor shame, nor any social pressure from his peers) to adapt his acting to what he genuinely perceives, or at least formally accepts, as right and wrong. From this point on, what you see is not only acting and re-enactment, but also, the reality of killing.

Take the scene of the burning of the village for instance. As they are getting ready to film, a veteran of the 1965-1966 massacres chats with his friends, talking about how he used to rape "communist" women back in the days when they were the law. As a spectator, naturally you are outraged. But the real chills come later on, when after the re-enactment of the burning of the village and the murder of its inhabitants, Oppenheimer masterfully sets the camera on the same old executioner. We see him from a distance, through a curtain of fire, smoke and hot air. He is now resting in a chaise longue, smoking a cigarette and laying back after a tiring day of filming. And then it sinks in. That image is a double folded reality: that is a man smoking a cigarette after a tiring day of rape and murder. Of course you know that it didn't happen, not now, but forty years ago, that is exactly what that man would have done. Because he is an executioner and not an actor, because his feelings and inner life are not of an actor playing an executioner, but of an executioner playing himself.

Plato comes to mind with his determination to banish imitative poetry (theater and cinema would qualify as such poetry in modern times) from his perfect city. The Greek philosopher argues that bad people tend to imitate bad actions and bad people and that, on viewing such an imitation, the spectator will he himself become bad. Therefore, imitative poetry should only limit itself to the imitation of good people performing good actions. By switching perspectives, what it comes to is this: bad people who have themselves done the bad actions they are imitating, are not imitating, but are doing. Take away those two seconds, the murderer resting, gazing through the fire he had started, and edit them on real live footage of an actual Indonesian massacre. The result is not real in the common sense of time-space continuity but, on a metaphysical level, one could argue that the two reels edited together are as closely connected as cause and effect can be.

Another example of this kind of chilling reality coming to life through fiction, is the scene in which we see Anwar Congo under a table, strangling an imaginary communist lying on top of the table. We don't see the man, he is obviously not there, the wire is not tied around somebody's neck. But forty years ago there was somebody on that table. And the skill and effort Anwar puts in this imaginary murder is the exact image of what would have happened during the massacres. Anwar himself realizes that when predicting the success of the movie: "there has never been a movie where people get strangled, except in fiction, but that's different, because I did it in real life."

But the high standard for this kind of disturbing cinema, that comes at you with the same intensity as reality does, is not set by the murderers. Early on in the movie, during a script meeting between the old gangsters, a middle aged man reveals himself as the stepson of one of the communist murdered in the massacres (though not by the hand of anyone shown in the film). How he got there is unclear, he is never credited, but Oppenheimer admits that he found out about the massacres when interviewing the relatives of the victims for his Globalization Tapes project. The man tells them his story in gruesome detail but assuring them that he is not judging in any way, he just wants to be sincere about it. Bearing this in mind, we see the same man delivering an amazing performance as one of the victims, being interrogated by the executioners. We also see the man playing one of the victims in the burning village scene, and then happily shaking the hands of the paramilitary after the shooting. In another scene, we see him yelling furiously "Cut his throat!" to the demon of Anwar's nightmares. A victim playing a victim and the murderers playing the murderers. It doesn't get any more real than this, and to top it all, the man gives such a powerful performance that he would qualify for an Oscar nomination and a psychiatric evaluation at the same time. Or maybe this is exactly that: therapy through art, the victim and the murderer, accepting what happened to them by going through the rituals of murder, through The Act of Killing.

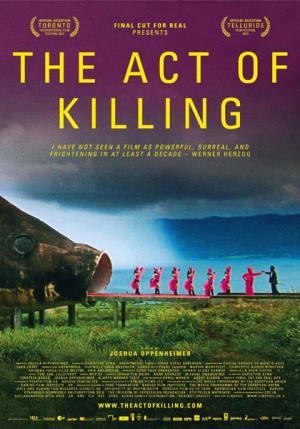

On the surface, this film could best be described as a making-off documenting Anwar's attempt at re-enacting his murders in various film genres: gangster, western and musical, all with a distinct Indonesian flavor and a (good) taste for grotesque (his sidekick, Hernan, plays the fatty love interest in many of these featurettes), black humor, that sometimes spills outside the frame of the movie within the movie, and all out surrealism. The scope of the film however is much more profound, and beneath all the surreal elements that the imagination of the old executioner conjures, what truly matters in this movie, are the real elements. At the same level of depth with that uneasy feeling I have talked about (that comes from knowing, that on some level, this is all very real), the camera seems to work in an opposite direction for Anwar Congo, not taking away a piece of his soul, but on the contrary, making his soul visible, for his mind and reason to deal with. An important part of the movie is made up of screening sessions and in the last one of these screening sessions, director Joshua Oppenheimer pushes Anwar on what seems to be, a tearful acceptance of his past. To the spectator, Anwar's repentance seems more a fear of bad karma coming his way. From a cinematic point of view, you'd want more, you'd expect his coming to terms to be more emotional, more powerful, not a result of the fact the director confronts him. You want him to convince you that he has found his moral compass, that he truly repents so you don't have to feel guilty. Guilty about getting to like this guy, this gentle grandpa who teaches his nephews not to harm little ducks, this funny old man who dresses like a pimp with a fashion degree, this Nelson Mandela look-alike and Sidney Poitier wannabe, this cinema gangster, this murderer. You want to be sure, you want the murky gray to turn black and white again. In fact, you crave for fiction (there is no such thing as a pure documentary, it is always someone's point of view), for an auctorial intervention that would edit some sort of moral meaning in this ending. But then you realize that this is exactly what this kind of cinema is aiming at: an emotional vertigo of reality that doesn't let you have the easy way out, once seen you just have to check it as something that happened, something real, not something that makes sense.