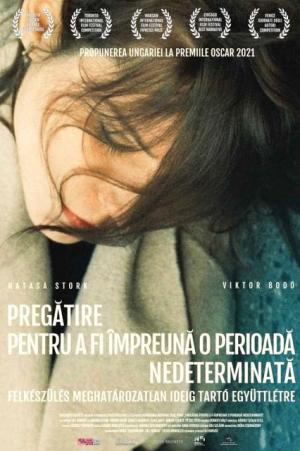

Six of the 12 films selected in the official competition of TIFF 2021 were included, at the end, received prizes during the Closing Gala. Surprisingly enough, the second feature film of the Hungarian director Lili Horvát, Felkészülés meghatározatlan ideig tartó együttlétre / Preparations to Be Together for an Unknown Period of Time, was not among them.

Born and emigrated from Hungary, Márta (Natasa Stork) is 40 years old and has a brilliant career in neurosurgery in America. While lecturing at a conference, she finds herself closely watched by János (Viktor Bodó). In a few weeks, her life changes dramatically. She decides to return to Budapest, to a job at a local hospital and to rent an apartment overlooking the Freedom Bridge, the one next to which János fixed a date on a certain day, at a certain time. Only that János doesn't show up for this second date and, when he meets her in the hospital, he pretends not to know her.

Part of what happens next in the movie is predictable and mediocre. Initially viewed with a mix of mistrust and envy, Márta earns the respect of her colleagues through some remarkable medical advice and interventions. A typical professional success story, as one can see thousands in movies with excellent box-office.

Part of what happens next in the movie would be predictable and mediocre if Preparation... were a movie made for box-office. Fortunately, Preparation... is not that kind of movie and this fact turns the evolution of the central character's personal life into a real revelation. Because Márta, a well-educated middle-class representative, carefully keeping the balance between reasoning and feeling and that between reality and dreams, asks herself the most logically-justified questions, suspecting herself suffering from illnesses diagnosed according to her scientific background and practice.

Two emblematic phrases summarize the way in which Márta understands to solve the great dilemma regarding the sharp and almost convincing way in which János conveys to her that she is wrong thinking the two of them have met before. "My opinion is that you came to me hoping that I would diagnose you with a serious medical problem that would explain János' reaction and would confirm your suspicion that the meeting of the two of you in America existed only in your own imagination. In fact, you don't have any medical problems", the psychiatrist tells Márta. Briefly put, Martha is not crazy.

And yet, throughout the film, the question regarding the authenticity of the meeting in America floats like a mystery in thriller. Did it really happen or not? Are the heroine's memories real or are they the fruit of her imagination, produced by the great desire for happiness? And us, the audience, we also start sharing Martha's doubts. We also begin to believe that it would have been too good to be true, and that, sooner or later, something bad will happen and will confirm the woman's self-doubts.

The way the movie solves the mistery in the end (based on a somehow predictable monologue and on a beautiful, yet maybe too metaphorical image with a huge speaker hanging many meters above the asphalt) is not so important. The key-question for (maybe) many of the people in the audience is the following: how did we come to doubt ourselves on such a large scale when our road to happiness turns out to be bumpy? A top specialist in one of those professions that ennobles the human species ends up doubting her own perceptions and memories when facing the man's refusal to accept a reality that is more than obvious. And we, the spectators, share the doubt. She does not believe in herself, we do not believe in herself, we do not believe in ourselves. The age of self-doubt is here!

Something keeps Martha in János' physical proximity. Something inexplicable and unexplained lends a crutch to the woman who lost the ability to imagine her personal happiness and fight for it. However, what it is inexplicable may be present today and may be absent from tomorrow onwards. So, what's left? What's left for us apart from ourselves? And what are we when we lack the instinct of hoping more than despairing?

Us without us - Felkészülés meghatározatlan ideig tartó együttlétre / Preparations to Be Together for an Unknown Period of Time in TIFF official competition, 2021

Mihai Brezeanu

Resurse

Alte articole de Mihai BrezeanuCronici ale altor filmeArticole similare

Un film românesc îți arată puterea distrugătoare a internetului - #dogpoopgirl / Iulia BlagaCatcher in the poppy field sau De veghe în câmpul de maci / Roxana PavnotescuVedere de sus cu înger și dronă - Neidentificat / Roxana PavnotescuComing out-ul se amână - Câmp de maci la Premiile Gopo, 2022 / Cristian CaloianBun de tipar - Întregalde / Lucian MaierToate articolele despre Festivalul TIFF 2021Toate articolele despre Felkészülés meghatározatlan ideig tartó együttlétre / Pregătire pentru a fi împreună o perioadă nedeterminatăScrieţi la LiterNet

Scrieţi o cronică (cu diacritice) a unui eveniment cultural la care aţi participat şi trimiteţi-o la [email protected] Dacă ne place, o publicăm.

Vreţi să anunţaţi un eveniment cultural pe LiterNet? Îl puteţi introduce aici.

Publicitate